Food for thought — trending in fashion meets foodie disruption.

Until now, at the consumption level, startup-led innovation has been centred around either convenience (delivery apps, rapid groceries & meal-kits) in keeping with our busy schedules, or alt-proteins (plant-based, cultivated meats & precision fermentation) for a more sustainable future. In fact in 2017–21 delivery apps received over 60% of all VC food tech funding (~£11bn).

If 2023 is going to be a golden vintage for food-related VC investments, then who will the next big players be, and what will they be doing?

The investment landscape in foodtech has changed considerably in the last months. Major valuation shifts across the VC spectrum have forced reconsiderations in prioritising profitability over growth, which in an industry defined by the movement of physical goods (i.e. perishable food), with a reliance on global supply chains, high amounts of energy and heavy machinery, makes the opportunity to create value from thin margins a complex feat. Nonetheless, the sector is still ripe with opportunities to innovate, digitalise and make more sustainable.

The next generation

Ever since the inception of #foodporn and “the phone eats first”, social media has become a central companion and influencer in our relationship with food. It has broadened our palates, and brought fame to Salt Bae, whipped coffee and smash burgers. Over a third of Americans claim that social media has influenced the way they cook at home, and the evidence is reinforced by Instacart’s observed shopping habits, in which viral recipes ended up in shoppers’ baskets much more frequently.

Why do food and social media go hand in hand? — The logical answer is that food is intrinsically social and has historically been so. Food has always been at the centre of communal celebrations, an opportunity to share and create. Not only is it essential to our survival but we also enjoy the process of eating, and even more so when we eat with others together. Social media provides the means to share one’s own culinary creations in return for external validation, and in fact 20% of the millions of food photos shared daily are for this exact purpose of vanity.

So if we are intrinsically vain and conscious of others perceptions of what we eat, then we could start drawing parallels between food and fashion. Where this becomes relevant (rather than ridiculous) is when looking at some of the social-led innovations that we have seen in the fashion industry: Instagram and other social commerce (promoted content and influencers), peer-to-peer reselling (e.g. Depop), transparency of supply chains (e.g. Everlane). Is the food industry about to catch up with fashion on these trends?

Social commerce, but for food

Social commerce is a phenomenon with its roots in the fashion world: brands, who had found big success in social media marketing using influencers, were still facing friction between a customer seeing a product, and them actually hitting the checkout button. Too many steps between product discovery and payment lost many potential customers along the way. Reducing friction is not the only benefit; with Instagram, Facebook and Tiktok now acting as virtual storefronts for fashion brands, their users see social proof in products through likes, comments and shares of friends and influencers, providing the purchaser even more confidence.

We may actually not be far off already: According to Will Shu, founder of Deliveroo, the next key differentiators among delivery platforms will be the ability to transition from a transactional process for users to a more emotional experience. For example the use of video content on the discovery page, turning the unexciting search for your next delivery into a more interactive and engaging experience. Imagine seeing the melted cheese ooze out of that burger, just like in a TV ad, with an order now button right below. Could a focus on the augmentation of physically eating be the next movement?

But how will this be taken further? The use of video content alone lacks the social interaction piece in which validation from peers or influencers can encourage you to try a new dish. Next time you hit the ‘like’ button on a viral Tiktok, will the ingredient list be automatically added to your grocery shopping list? How can delivery platforms leverage reviews in a more powerful way, beyond the 5* rating system?

Whilst this may just sound like a marketing innovation, it could also have further positive consequences on our relationship with food. If we are able to use this media infrastructure to bring the end consumer closer to the origin of the food, and provide them with an understanding of how and where the food is produced, who is involved, how far is it shipped etc. we could start to see a new generation of deeply conscious consumers.

The case for peer-to-peer in food

Tiktok caught onto the fact that their platform had become a central point of influence for new recipes and entered a partnership with Virtual Dining Concepts, launching in hundreds of dark kitchens across the US, selling creators’ prepared viral dishes via delivery apps. The concept involves paying some royalties to the original creators of these recipes, which has in essence created the foundation of a large peer-to-peer marketplace for new dish creations.

Besides Tiktok, and in another parallel with the world of fashion, there are a number of food start-ups breaking into peer-to-peer based models. But unlike clothes, food is not so easy to produce safely, recycle or reuse. Instead the short shelf-life of foods, the certifications, safe handling and refrigeration requirements all pose greater barriers to a perfect, wasteless circular supply chain. Despite these barriers, there have been some recent examples of founders finding a P2P model that works with food:

- Delli — launched by the founder of Depop to be the ‘Depop of food’ — a marketplace where independent cooks or food makers can sell their creations, and connect with a community of foodies

- Olio — originally launched as a community driven sharing network of household foods that would otherwise go to waste, bringing P2P circularity of unwanted goods within communities. It has since expanded into more household categories

Are there further P2P models that could work in food? The Olio model could be replicated to work at a B2B level between restaurant kitchens with surplus ingredients before they expire for example.

Is there an education angle?

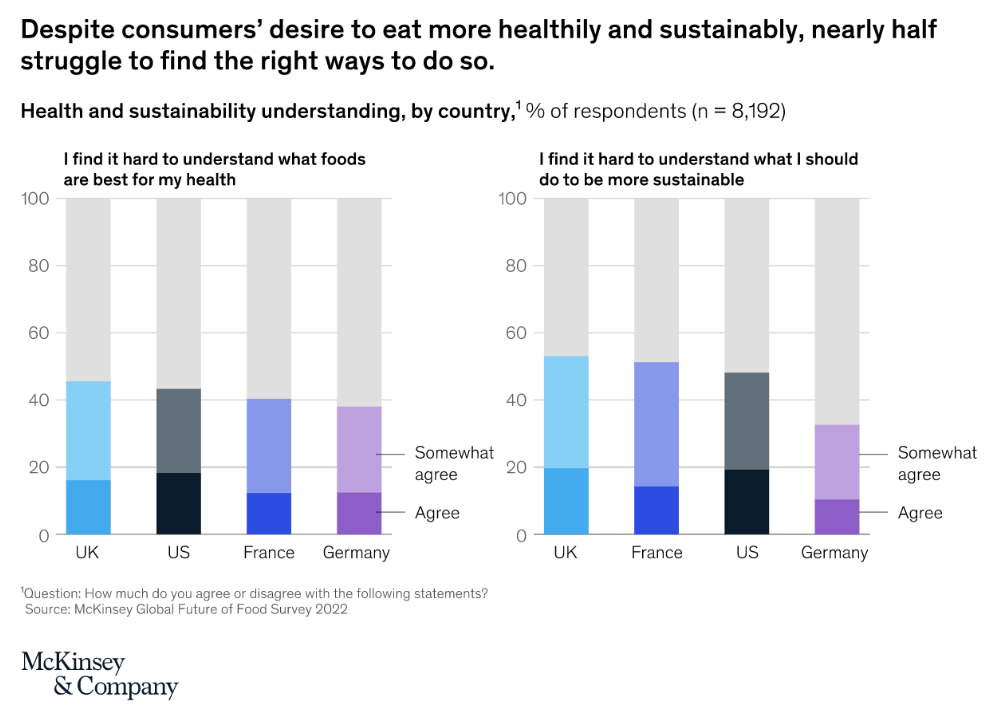

Whilst clothing brand choice does not usually have direct health consequences, the need for wider consumer education in food is clear — diet-related diseases are more prevalent than ever and whilst many want to do something about it, a McKinsey study revealed that almost half struggle to find a way to do so.

If we are able to bring end-consumers closer to and more conscious of the origin of the food they eat, as Everlane has done for fashion, we would enable them to make better choices, in line with their values. The information gap and opacity of the decades old food supply chains currently prevent today’s consumers from making their values have an impact further upstream.

At Collectiv Food, this is one of our key areas of focus — we collect digital content from the suppliers we work with, as well as multiple data points on sustainability via Responsibly, which our restaurant customers can access and learn about the provenance and production methodology of the food they cook. Through digital menus, diners at these restaurants will be able to explore the story of the food served, feel closer to the products they consume and know to feel good when they represent their own values.

Facilitating this sharing of information, and providing full digital transparency from farm to plate enables a new and ever closer relationship between end-consumers and the food’s source.

Today, in the traditional analogue supply chain, the information is lost at the different levels. However, there is an opportunity to build this data infrastructure between producers and consumers, and once this has been set up, there will be some exciting new opportunities to digitally augment dining experiences in the future. Food producers will have a platform upon which they can share their good practices and market their quality through digital content — video or other — playing a more direct role in the shortened food supply chain. Customers will be able to advocate for change more easily and impact the upstream more directly.

In the future we should not need a Netflix feature on the environmental impact of fishing (Seaspiracy) to reveal the intricacies of certain food supply chains but at the same time, full transparency should be encouraged, even if positively imperfect — we prefer to see the truth.

Tobias leads strategy at Collectiv Food, focussing on growth, data and fundraising. Special thanks to MSM for their insights and comments on drafts — as early investors in both OLIO and Collectiv Food, they have a particular interest in the nexus of food, circularity and social, and what might emerge next.